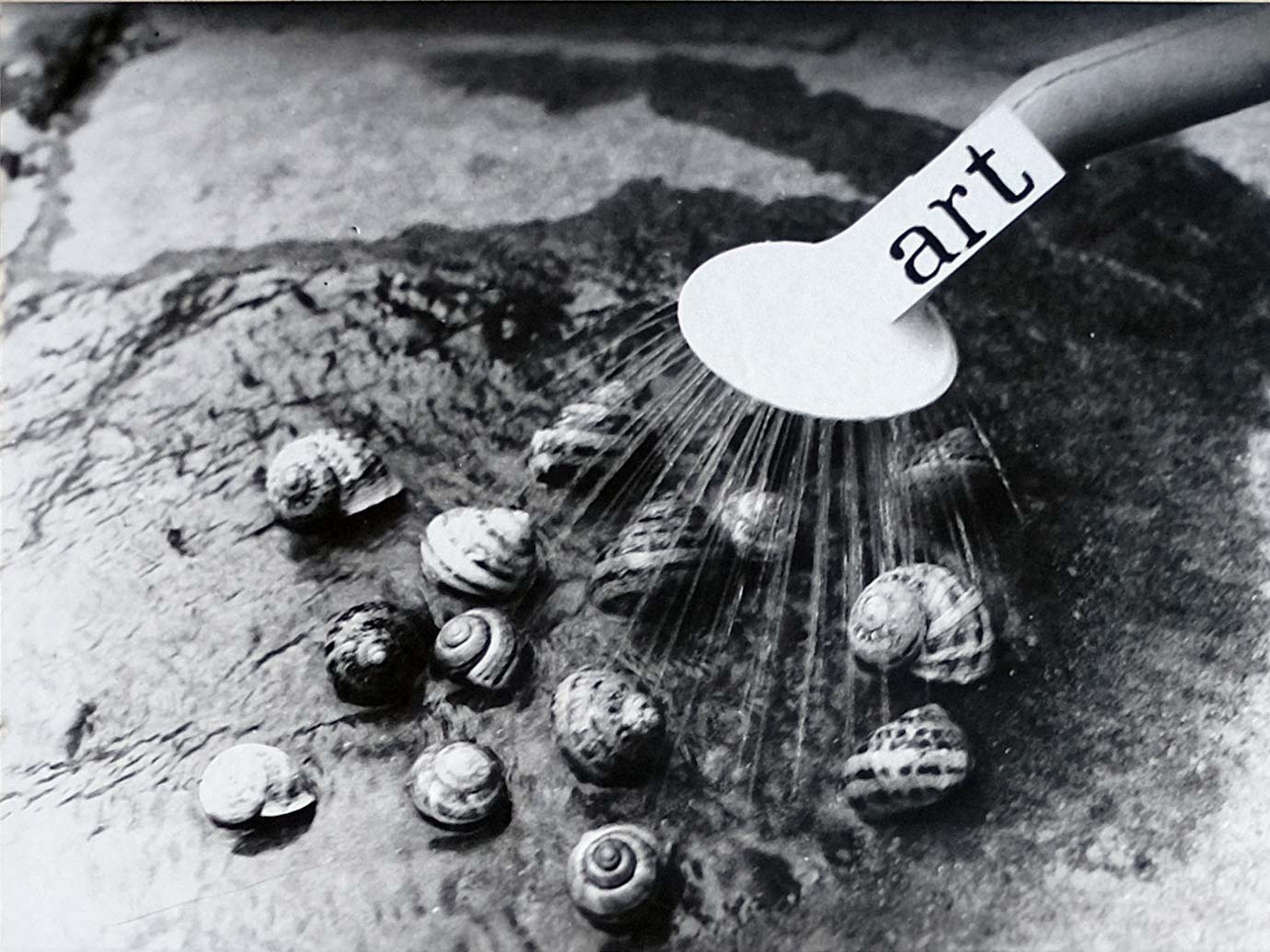

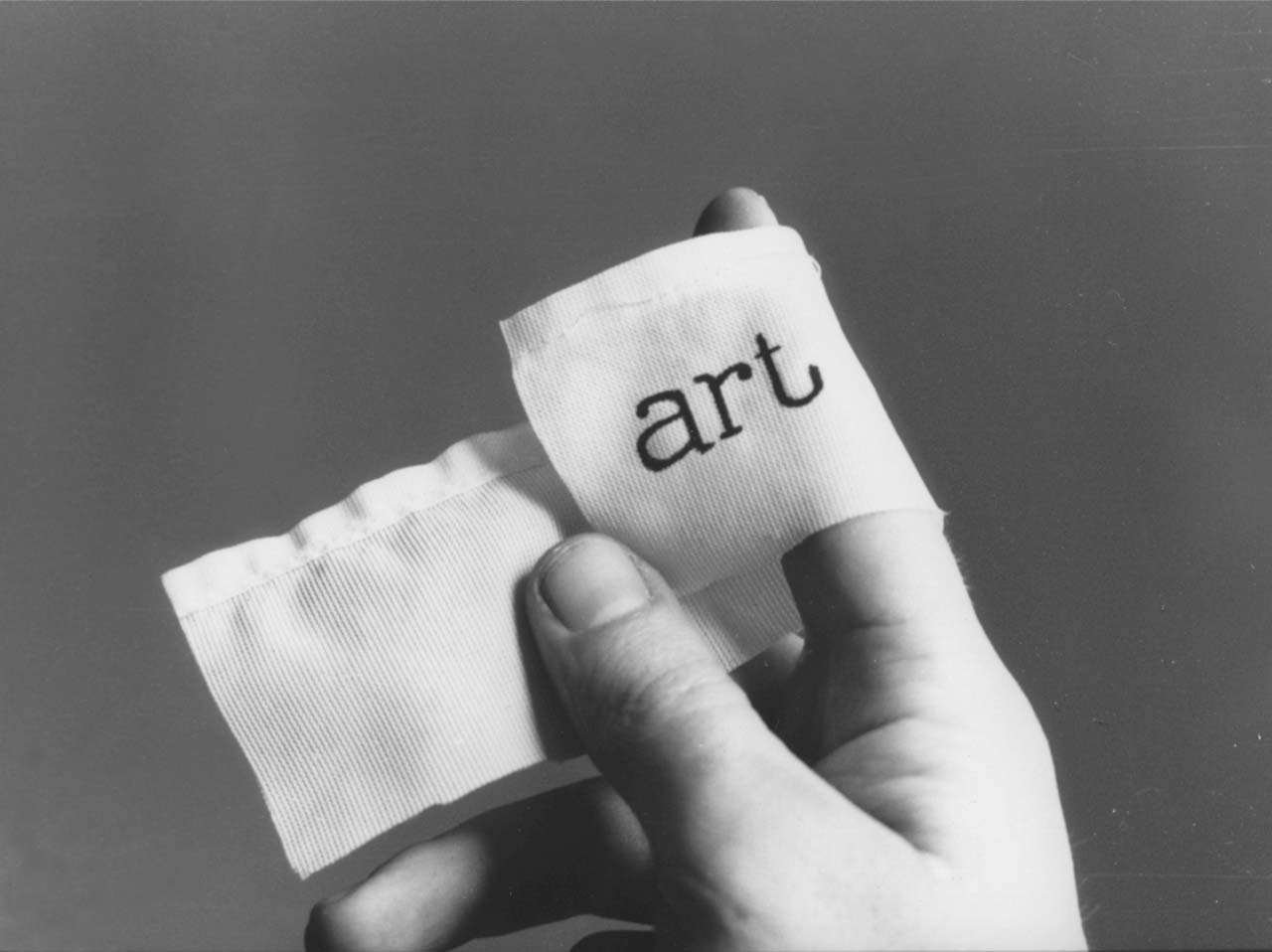

In 1971, I tried to incorporate the creative method I had first adapted in the Five Books, the ultimate reduced form of artistic expression called conceptual art, into a unified genre, and I decided that whatever I did, I would always choose photography as my language. Like many other artists who worked in the field of conceptual art in the 1970s, I was looking for a basic motif as a starting point that could replace the entire cosmos of fine art, and I found this – very simply – in the word “art”. I thought that the concept of “art cosmos” – which could stand for the entire realm of art and all its conceivable forms – could be most easily illustrated by the word “art” written on a little ball.If I have a ball like this, all that’s left is to start playing with it, and the rest will be brought about by chance or so-called “life”. All the events and adventures that normally happen “life-size” in the real world to art itself and to the artists who serve it can also happen to the little ball.

It’s been almost half a century since I took a whole series of photos that served this programme, and now it’s time for me to ask the question: Did I manage to achieve my goal with these photos? Did I really manage to relate in an infinitely reduced form all that could be the fate of art?

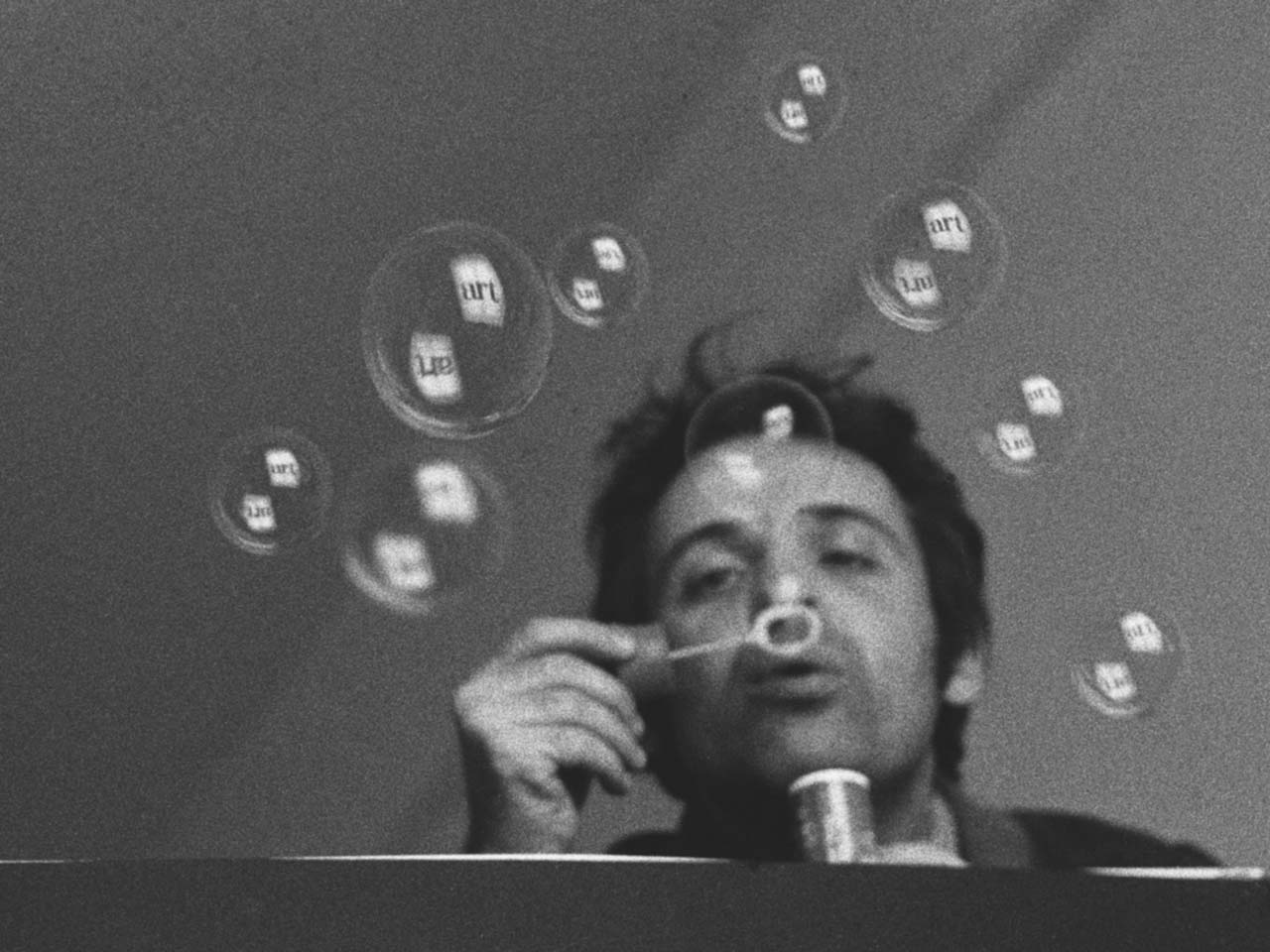

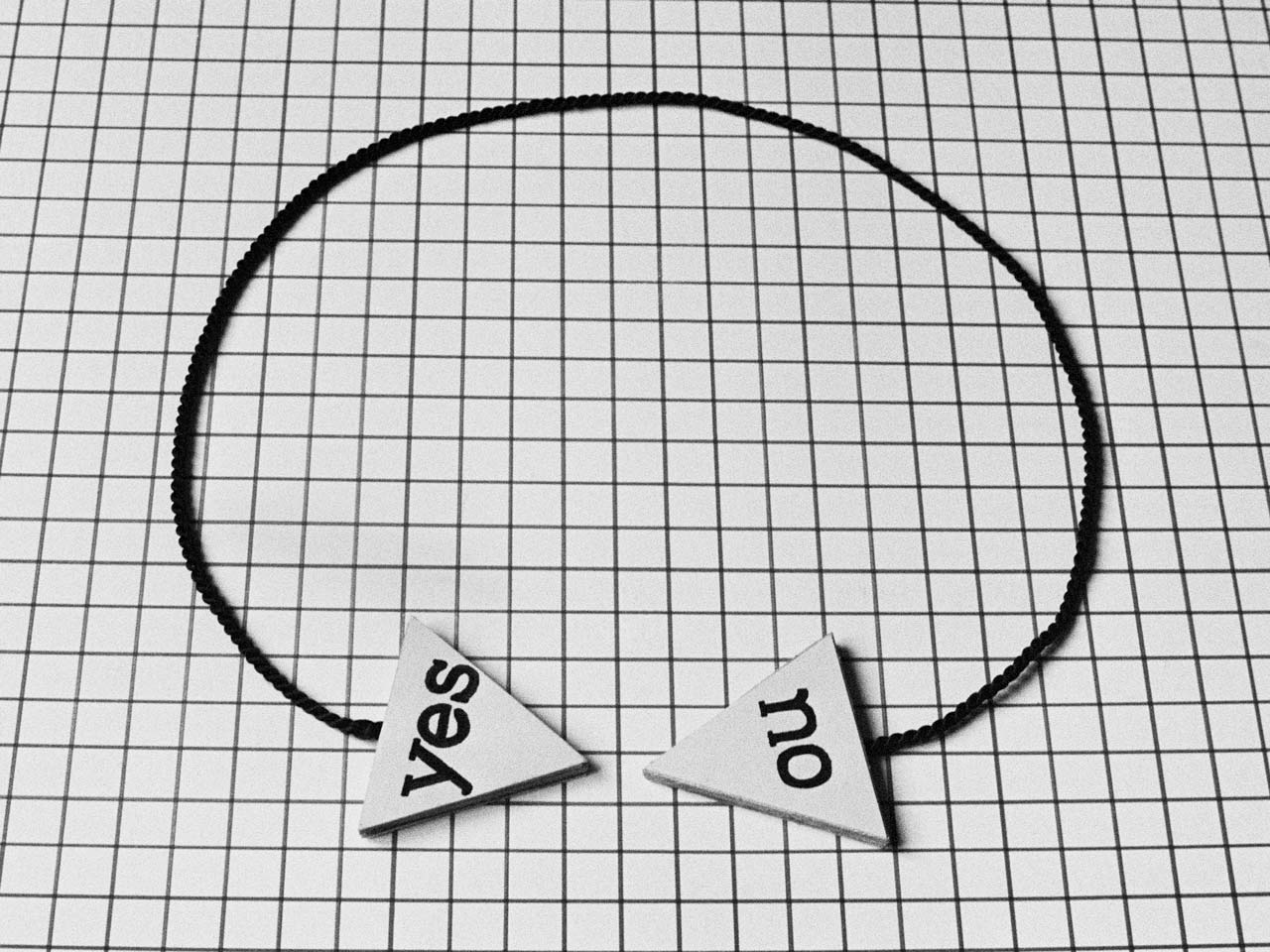

The answer is not simple. Today, after so many years, I can see very clearly that the whole series fits well into the definition that these images are actually allegories. That is, these are not just depictions that can simply be called symbolic, but scenes that immediately contain some “lesson” or moral. The art-ball sinking into the water (sea ...) naturally symbolises the sunset, but it can also be the symbol, the allegory, of the “eve”, the passing or end of art. The Kokoo [sic!] photo, which shows a bird’s nest with some eggs, chronicles that the cuckoo was there and laid its odd egg among the eggs of the little songbirds – the cuckoo’s egg will hatch before the other eggs, and the newly-born bird will eject its step-siblings, the other eggs from the nest. However, this selfish little cuckoo is art itself – so would the lesson of the photo be that art is a parasitic being? That is, this photo is also an allegory with a moral. The most dramatically coloured moral is in the soap bubble on which the word “art” is reflected, as it is also about the death of art: “...evanescent like a bubble ...” as we read in an old Hungarian poem. The scene of the children blowing bubbles was a common pictorial theme in the 17th and18th centuries and a requisite of religious paintings collectively referred to as “vanity” pictures.

With this photo, not only did I find another symbol for the fate of art, but – although I had no intention of anything at all – I also managed to resurrect a baroque art form that had become extinct in the 19th and 20th centuries. I can tell you that this shot was a fortunate coincidence. Because although its moral is about transience, the image of bursting soap bubbles has become a significant audience success, and this photo has kept the entire Art Series alive ever since.

Text by Géza Perneczky, in: Géza Perneczky, The art of Reflection, edited by Patrick Urwyler, Verlag für moderne Kunst, 2020, p. 33.